#34 We are not a materialistic society

It's clear that we don't value material things enough - and it's hurting our planet

Hi, I’m Florencia Lujani and this is a new edition of Cultural Patterns, a newsletter on brands, culture and strategy. I’m also increasingly looking at how these are impacted by the climate crisis. My posting schedule is a bit random, so if this is the first email you receive from me, welcome! Feel free to reply to this email and get in touch. Florencia x

Advertising is fundamentally a meaning-making practice: we transform material objects into cultural signals, combining a brand with highly valued meanings to differentiate, create a common understanding and put a premium on price. But as the importance of the symbolic has intensified and expanded, the materiality of consumption and its utilitarian function has become less important. This has shaped consumer culture in a fundamental way, as the famous cultural critical Raymond Williams said:

Our problem isn’t that we’re too materialistic; it’s that we’re not materialistic enough. We de-value the material world by excessive acquisition and discard of products.

This is the third article on the relationship between brands, consumer culture and the climate crisis (here’s Part 1 and Part 2). This time, it’s all about the illusion of the dematerialised economy.

From products to experiences

In the last decade, brands started investing a lot more £ in experiences. It was a move that came from the idea that the economy was becoming less “material” - that people were more interested in symbols (images, experiences, signs etc) over material goods.

This wasn’t just a marketing perspective, it was present across many different spheres of culture. Back in 1970, Jean Baudrillard famously said that what people consume is the meaning or symbolic dimensions of goods, rather than goods as physical objects. Later in 1989, political scientist Ronald Inglehart argued that consumers were increasingly post-materialist, where the material properties of goods are eclipsed by signs and symbols, experiences, and images.

With the infamous “X% of millennials prefer experiences over products” stat, the world domination of the PR-led ‘Instagrammable moment’ and millennial-pink interior design began.

Museum of Ice Cream in Singapore

Selling symbols

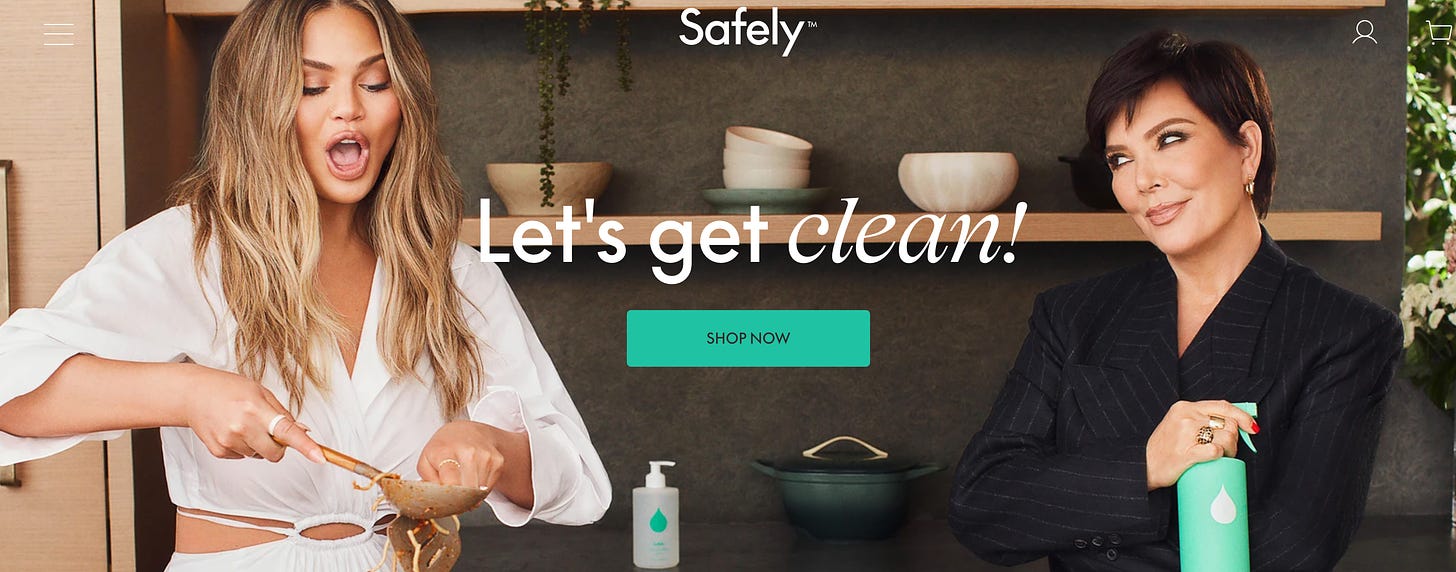

Then a few weeks ago, Kris Jenner and Chrissy Teigen launched a new cleaning brand, Safely, which made me think of the material consequences of selling symbols.

Safely sells “plant-based, concentrated products with ‘natural uplifting scents”, and if the premise sounds familiar, it’s because Ecover, Bio-D, Method, and other brands already sell plant-based and eco-friendly household products. This product isn’t new in any shape or form: it’s just selling aesthetics, symbols and ‘vibes’.

Safely can only be described as ‘peak pandemic’: a glamorised idea of cleaning led by the 1%. It’s one example of the dematerialised economy: a new brand that leverages celebrity status, portrays images of aspirational and romanticised mess, and offers nothing new but aesthetically pleasing packaging for your cleaning cabinet. But this brand has a tangible impact: it uses up natural resources, adds more plastics to the market, and generates more pollution.

Out with the old, in with the new

But in the context of the climate crisis, the dematerialised economy needs to get material again.

The issue with brands like Safely is that they’re part of the sign economies, so they’re vulnerable to the dynamics of rapidly changing symbolic value.

As what is fashionable remains so for a short period of time, then new fashionable items need to replace those. This means more utilisation and exploitation of natural resources because behind every symbolic good there’s a material one.

As Juliet B. Schor notes, a materiality paradox arises: when consumers are most hotly in pursuit of non-material meanings, they are most prone to use up natural resources

Sharpay Evans, iconic queen from High School Musical, would say:

Fourteen years later, ‘Fabulous’ is still a bop and nobody can say otherwise

Getting material

Creating branded symbols and being creative is a great job. Last week I was fascinated by the responses to this tweet asking people to share their favourite thing about McDonald’s: it’s all emotions and memories tangled up in a messy network of symbolic associations.

But I’m increasingly as interested in understanding material and invisible aspects of consumption: who creates the product (workers conditions), what it’s made of (natural resources), the factory in which it’s produced (supply chain), where in the world it comes from (transport), etc. As strategists, we need a rounder view - we need to understand the whole economic and environmental impact of brands.

We have to come to terms that when we sell aesthetics and symbols, the environmental impact is very real. I’m looking at ways of being more materialistic in my approach, and implementing this eco-effectiveness framework seems like a good first step, but I’d be interested in your ideas. Got any? Please, share them with me on Twitter, Linkedin, or you can reply directly to this email :)

Until next time,

Florencia

Read my #Growthmania series here:

Part 1: The mandate of economic growth and why we should build businesses for permanence, not performance

Part 2: Growth vs development: brands experimenting with generative business practices

Part 3: This article :)

FKA twigs wearing celebrities’ rubbish

👋 Hi, thank you for reading again. Hope you’re enjoying these articles on the relationship between brands, consumer culture and the climate crisis. Thank you to those who got in touch in the last couple of months! Meeting other like-minded people is always a treat. I had an amazing chat with the super-smart, all-female team behind Mac&Moore, a brand consultancy for businesses that want to do well and do good.

🤓 📚 Besides work, I’ve been neck-deep in the academic world. As part of my Master’s Degree in Cultural Studies, I did a module on television and just submitted a 5,000-word essay on WandaVision and the global influence of the American sitcom throughout the decades. I’ve turned it into a Google Slides doc that you can check out here. I also just submitted my proposal for the 15,000-word final dissertation, and it’s a long project, so one of two things might happen… either you’ll get a lot of writing from me as I go along, or I’ll take some time off to finish that mammoth of a project. Who knows :) See you around!