#42 The power of ordinary culture

how everyday life holds the key to strategic relevance and creative impact

If you work in advertising, you know that the industry is obsessed with the niche and new. In the fifteen or so years I’ve been working in advertising, I’ve heard too many times about tiny signals that are supposed to ‘revolutionise’, ‘reimagine’ or ‘transform’ consumer behaviour. And every time, this has reinforced my belief that as strategists it’s our job to stay firmly grounded in mainstream territory, while also being able to spot and capitalise on the emergent.

Yes, new things are exciting and offer a competitive edge. But sometimes it feels like the rush for the next is all there is. That’s why I’m dedicating this piece to the wonderful, and sometimes undervalued, everyday culture. The cultural artefacts and practices of the everyday (from popular media to fine art, from family life to politics) should be treated with the same care and interest as the niche and emergent, without diminishing its creative and intellectual dimensions. Ordinary culture is rich with opportunities for effective communication, and it’s right there, ready to help us achieve maximum impact.

So in this article, I’m borrowing the theory from Raymond Williams, leading scholar of British cultural studies, and the sensibility of Martin Parr’s photography, to illustrate its power. Let’s get into it.

Why is culture ‘ordinary’?

In the list of writers that have influenced my thinking, the cultural theorist Raymond Williams (1921-1988) is up there. He was the son of working-class parents from a Welsh border village, and while he became a figure in the highest academic circles, his upbringing shaped the way he understood big words like culture, class, democracy and more.

He wrote ‘Culture is ordinary’ in 1958, and it blew my mind in the way only timeless writing can. He argues that culture is a fundamental part of everyday life, created and sustained through people’s daily interactions and activities. He says:

“Culture is ordinary: that is the first fact. Every human society has its own shape, its own purposes, its own meanings. Every human society expresses these, in institutions, and in arts and learning. The making of a society is the finding of common meanings and directions, and its growth is an active debate and amendment under the pressures of experience, contact, and discovery, writing themselves into the land.”

As society evolves, these shared meanings aren’t fixed - they’re debated, challenged, and redefined over time. This process isn’t passive, but is one of active engagement: questioning norms, updating values, and reshaping the collective story.

Culture is all the small but telling habits that structure our daily interactions: it’s the way we greet each other, how we prepare for a date or night out, the brands we choose, how we name our Whatsapp group chats, the rituals around work and leisure, and more. Crucially, culture is not just ‘the arts’, the domain of the elite or the educated, but of everyone:

“There is not a special class, or group, who are involved in the creation of meanings and values, either in a general sense or in specific art and belief. Such creation could not be reserved to a minority, however gifted, and was not, even in practice, so reserved: the meanings of a particular form of life of a people, at a particular time, seemed to come from the whole of their common experience, and from its complicated general articulation.”

What a democratic, equitable and inclusive way of thinking about culture. Williams believed that greater understanding and appreciation of culture can help to promote social cohesion and also serve as a means of resistance. And how do we need social cohesion right now!

What culture really looks like

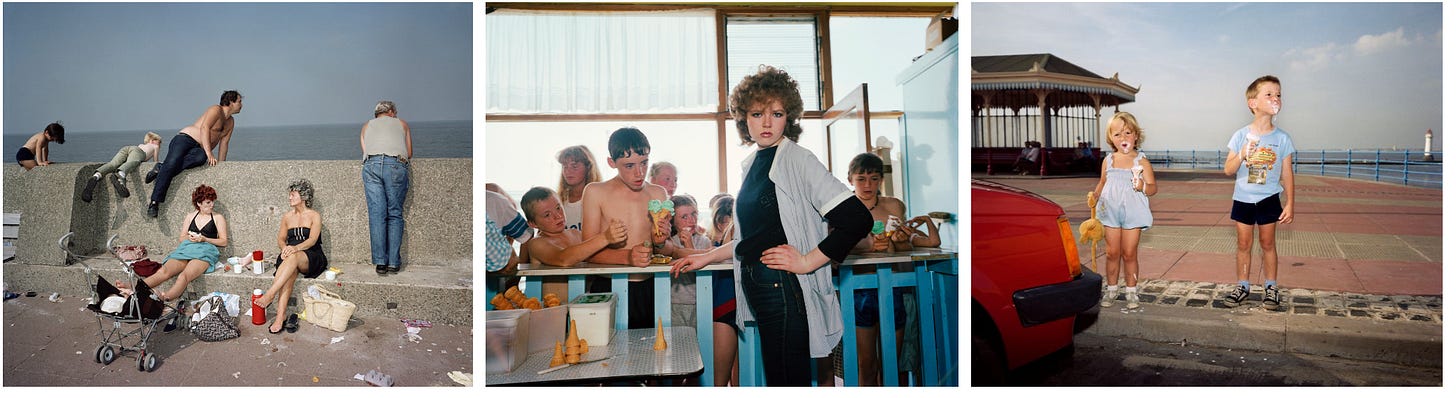

Martin Parr is one of the world's most famous and successful documentary photographers. In a time where ‘sophisticated’ and professional photographers only shot in black and white, his brightly-lit and colour-saturated style disrupted the scene by capturing Britain’s class system like no other. His most famous work is The Last Resort, a series of pictures he took between 1983 and 1985 of people enjoying themselves at New Brighton beach, in Liverpool. Even though he has captured tourists, the working-class, aristocrats, the middle class, models, and people of all walks of lifes, the reaction towards his work was never straightforward:

“A lot of people don’t like my work. They’re blaming me for seeing shabby conditions. With The Last Resort, we showed the work in Liverpool in ’86, and no one mentioned this idea of it being exploitative or cynical. But when it went to the Serpentine, that’s when that all happened. People in the south-east, they don’t know what it’s like in Liverpool, because they’ve never been.” Full interview

Parr juxtaposes the people’s reactions in Liverpool, who were seeing themselves photographed, and that of audiences in the Serpentine, an art gallery in Hyde Park, London. This distinction between lowbrow and highbrow culture are obsolete and irrelevant in the digital age. But to me, his approach to photography is one of the best examples of capturing the mainstream with respect, no judgement. He truly sees people, and so he exposes the social fabric, which many times is messy and ridiculous. His photographs are layered, and the focus isn’t solely on the person being photographed, but their social context too. In doing so, his work reveals that the everyday is complex, deserving of care, reflection, and critical analysis.

Ordinary life, extraordinary meaning

I chose two photographs from Parr to do a bit of cultural analysis on, and illustrate why the ordinary can still provide endless opportunities for strategy and creative ideas (this is the first time I use the video feature)

This photograph was taken at Dunston Social Club, in Newcastle in 2008, but it could be anywhere in the UK. These places are not glamorous, but they have so much meaning: you can feel this couple has danced there countless times before, and there is a sense of continuity, of engaging in a ritual sustained over time. The local drummer providing the live music is much younger than the dancers, so this social club is for everyone. The Union Jack is there to represent the communal identity, and is casually hung, without much protocol. These elements represent what Williams called the residual, cultural forms from earlier periods that remain vital in the present. It might be unassuming, but the scene is layered with memory, tradition, it represents lived culture.

This is a girl’s night out in 2009 in Bristol, but the photo could easily be from today if the hairstyles and fashion weren’t so clearly late oughts. Young women partying, smoking, and laughing in the street *are* culture in action. The city and the night-time thrills invite the ladies to express their femininity with freedom, their presence is unmissable. Their appearance, gestures, and interactions all very similar, almost like a group performance. Williams said that our bodies are ‘forms of embodied cultural knowledge’, because the way we move, dress, and exist in our bodies is culturally learnt. What I love about this image is that they’re clearly not paying the slightlest attention to the photographer, they are deep in conversation, completely unbothered by any outsiders, and having the time of their lives.

Everyday life is full of meaning, and the things we consider ‘normal’ are actually always worth thinking about and considering. If you think culture only comes from the fringes, is the domain of the elite, or is only found in the arts, then your comms will be missing out.

The mainstream isn’t boring, it’s where meaning is created and contested at scale.

Mass relevance is a creative superpower

Let’s link it back to communications. The ordinary is super powerful in communications because it is the dominant culture (its well-established norms, routines, and shared understandings) that drives most decisions. Of course, there are many new factors influencing new behaviours, but in the majority of cases, it’s the ordinary that guides behaviour. By engaging the majority of people, the mainstream moves the needle.

If you do commercial work, engaging the mainstream is the basis for the ‘light buyers’ theory, which has been extensively investigated since the 1970s by the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute. For those outside the marketing world, here’s the short version: most people don’t buy any one brand all the time. They have a handful of acceptable options and switch between them, often buying that selection of brands just once or twice a year. This means most people are ‘light buyers’, and these make up the bulk of a brand’s customer base. Big brands grow not by cultivating deep loyalty from a small group, but by being chosen just a little more often by a lot more people. That’s why appealing to the mainstream matters: it increases the number of people who consider you. Brands like Allbirds, Harry’s, Clif Bar and Lush grew by shifting from niche appeal to mass relevance, and it paid off.

If you work in strategic comms or campaigning, it’s the same logic. According to think tank More in Common, in the UK, the most progressive people represent only around 8% to 10% of the population. To make your cause relevant to the other 90%, you’re going to have to speak the language of the mainstream. If you’re familiar with my work at ACT Climate Labs, you know that we have developed an audience called ‘The Persuadables’ to bring this to life. The best recent example of this from the climate sector is this campaign about heat pumps. Pay attention to the families portrayed, the accents used, the different homes included. It’s the mainstream at its finest.

If something feels familiar, it feels more relevant too. Ads that tap into scenarios that are familiar (like family dinners, local humour, or recognisable social rituals) are more readily understood and remembered because they act like shortcuts in the brain, making the brand feel more present and accessible. That’s because they reduce cognitive load and feel “right” instinctively. When it reflects people’s real lives, advertising signals “we see you”, a powerful emotional trigger that creates a sense of belonging. That’s why this campaign from BBC Children in Need using backpack patches to convey children’s issues packs a punch.

And also, culturally relevant comms are more persuasive. If messages aligns with an audience’s cultural context (with their existing values, beliefs, and norms) people find it more convincing and trustworthy. Featuring people in ads that reflect our audience’s cultural identity can create trust and make people feel more understood, and therefore more receptive to the message. Climate charity Possible has just launched a ‘Cabbies for Climate’ campaign that fits perfectly here.

Bringing the ordinary into our work

I’ve already written extensively about cultural intelligence as a strategic asset, so it’s clear that I consider it super important to understandemergent signs and symbols, new practices, slang, behaviour, etc. This isn’t about choosing between the dominant and the emergent, because there isn’t one without the other. It’s about recognising that culture isn’t only made in the margins, it’s made and felt at scale.

So here are a few things to take into your next creative brief, strategy session, or brainstorm:

Start with what people are already doing. look at routines, rituals, in-jokes, habits, and other things people do with others, and explore them as creative opportunites

Don’t be afraid of the familiar. What feels “obvious” to you might feel validating to someone else, and will help you normalise behaviours and attitudes

Look for emotional weight in ordinary moments. A school run, a girls’ night out, a social club dance, these aren’t filler, they can allow us to explore topics like identity, memory, and meaning.

That’s the heart of it. Ordinary culture isn’t boring, static or unimaginative. It’s layered, generative, full of potential. When we treat everyday life with attention and respect, we open up space for resonance, scale, and creative possibilities that actually land.

So next time the brief chases the cutting edge, or the niche, or the new-for-the-sake-of-new, take a breath. Look closer at what’s already there.

That’s where culture happens.

That’s where people are.

See you next time,

Florencia

What are your thoughts? I’d love to hear some aligned perspectives and counter perspectives, both equally valuable. Get in touch with me by replying to this email, leaving your comments below, or on Linkedin / Bluesky.

Riding on the bus is a massively underrated activity. Zeitgeist-bathing, for a couple of quid.

This is a wonderful piece of work Flo 👏 and totally agree we need to look more at the mainstream. I think because advertising leans toward the progressive, and we forget that we aren't representative of the population, we miss the wood for the trees sometimes.